|

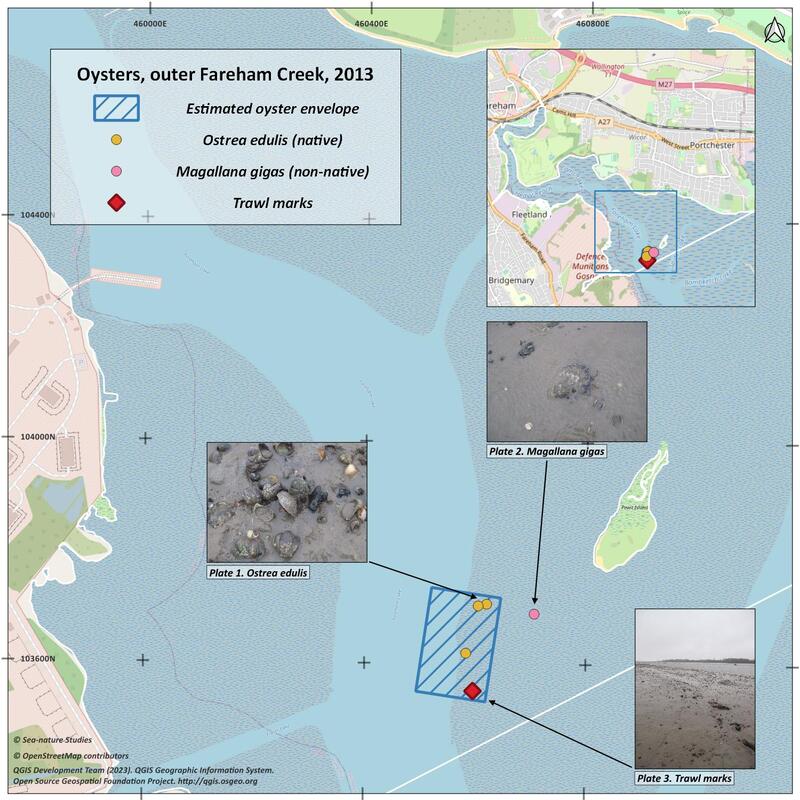

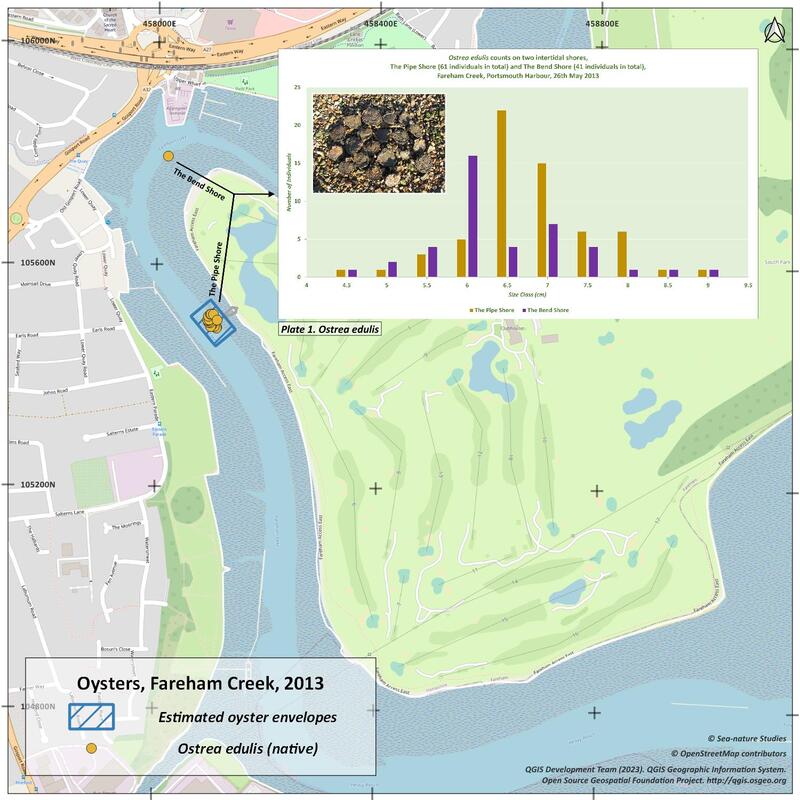

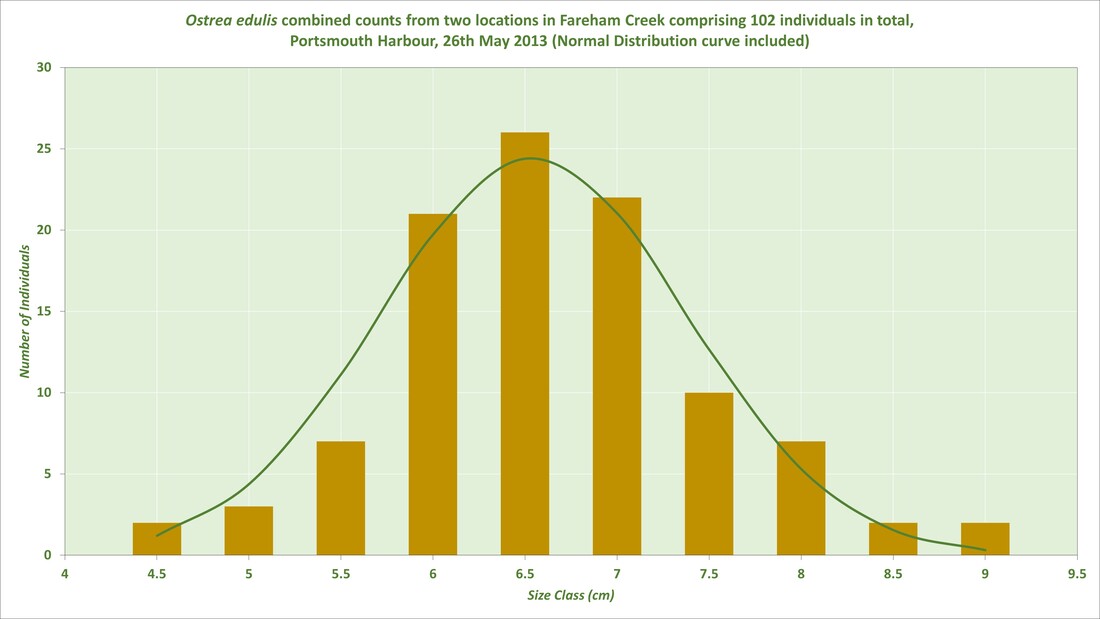

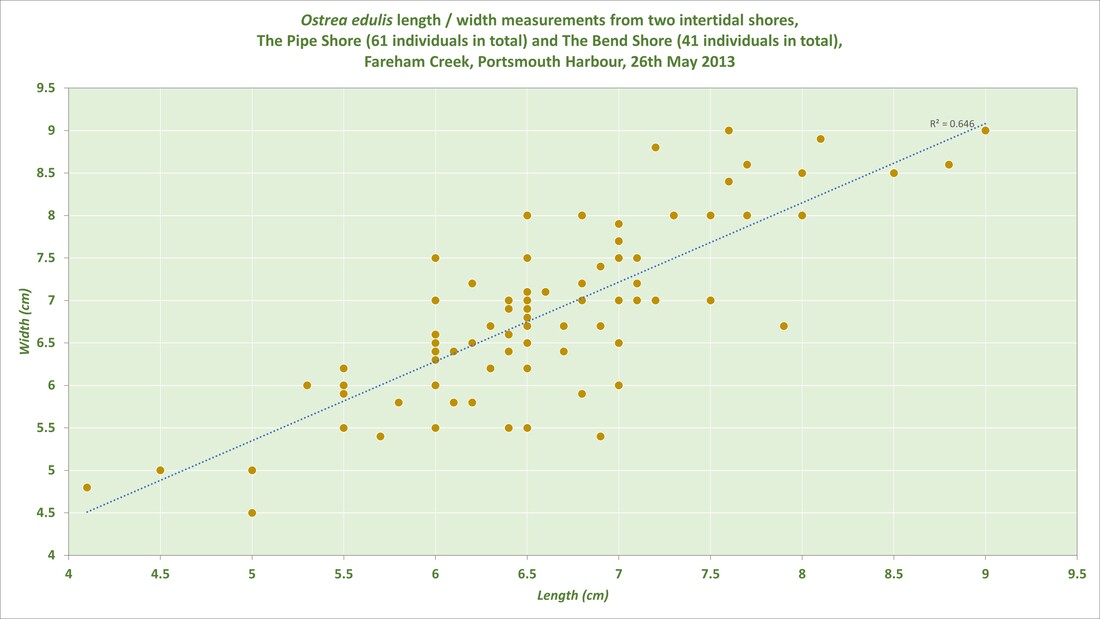

I must admit I got a little bit excited when Fareham Creek was one of the first sites to be recommended as a Marine Conservation Zone (rMCZ). The three Features Of Conservation Interest (FOCI) it had been selected for were: Native oyster beds (Ostrea edulis) – the Habitat FOCI; Native oyster (Ostrea edulis) – the Species FOCI; and, Sheltered muddy gravels – the Broad Scale Habitat. The ‘ecological description’ supplied by Balanced Seas (BS), one of 4 Regional Marine Conservation Zone Projects, started with this: “This recommended Marine Conservation Zone (rMCZ) would protect an area rich in native oysters and sheltered muddy gravels.” A little more background was provided in a BS Final Recommendations report: “The site covers Fareham Creek (also known as Fareham Lake) in the northwestern‐most corner of Portsmouth Harbour, where the River Wallington runs into the Harbour. It is considered by local fishermen and Southern IFCA to be an area rich in Native Oyster (Ostrea edulis) species and beds. Although no data were initially held by the project to verify either feature, the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust has confirmed the presence of this species by collecting and photographing specimens”. The same document noted, “the site has been selected due to the restriction on shellfish harvesting activities through a recent MMO byelaw”. Naturally, ‘considered by’ is not necessarily the same as strong verifiable evidence. In fact, the only actual hard data provided was garnered by the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust in 2011 as part of the MCZ project. The Trust confirmed the presence of the species with ‘8 species records (from 5 geo-referenced photos)’. That’s a plus and was duly submitted but, to cut a long story short, that plus was not big, and the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) duly swung its axe and that was the end of the Fareham Creek MCZ. I’m not saying it was an easy choice, but honestly, within the framework of the process, what else was going to happen? For me, that left many questions scattered on the ground. Just ignore them I thought, and get on with your day, walk away, it's done. But some questions are persistent and keeping surfacing, “What if there are oyster beds in Fareham Creek? It’s on my doorstep, surely it would be easy enough just to take a quick look in one or two spots, intertidally? Yes, yes I could do that, but hang on a moment though, first things first, what exactly, is an ‘oyster bed’? The Oslo – Paris Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic, OSPAR for short, has a useful working definition for what constitutes an oyster bed in their background document on the species (and yes, the United Kingdom has ratified the convention): “Beds of the oyster Ostrea edulis occurring at densities of 5 or more per m2 on shallow mostly sheltered sediments (typically 0 – 10 m depth, but occasionally down to 30 m) ”. Ok. Good. But we need to unpack that just a little because while the trigger value is 5 plus, the text clearly implies that densities of less than 5 are also 'oyster beds', just not ones that satisfy the necessary criteria for inclusion under OSPAR. So, the linked, relevant habitat, or biotope, as described by the National Marine Habitat Classification for UK & Ireland was given the code, SS.SMx.IMx.Ost. That’s a bit opaque to say the least so here’s what it is shorthand for: Ostrea edulis beds on shallow sublittoral muddy mixed sediment I know, it says subtidally, but this biotope can occur in the low intertidal area. The important thing is that for the biotope, Ostrea edulis is noted as being ‘Common’. Keep digging with me for a bit longer. What is ‘Common’ I hear you ask? That’s a particular label from the SACFOR scale. Oh dear, what’s SACFOR? That is an abundance scale, “… for recording the abundance of marine benthic flora and fauna in biological surveys. It has been used to describe the relative quantities of taxa in many of the biotope descriptions”. Each letter refers to a descriptor defined in the scale, so ‘C’ in SACFOR is ‘Common’. Job done, move on? Almost. What constitutes ‘Common for an oyster? Thanks for asking, because the values vary depending on the size of the organism, and for oysters it’s, 1-9 per metre squared (i.e. individuals 3-15cm in length). That's two, slightly different definitions of an oyster bed isn’t it? ‘1 or more per metre squared’ as in the biotope, or ‘5 or more per metre squared’ as given by OSPAR. Let's put aside the OSPAR definition and concentrate on the biotope which leaves the door a bit more open. But does that mean if I find one oyster and put a metre squared quadrat over that it’s a ‘bed’, just really small? That doesn’t sound reasonable, so I’m going to go ahead and suggest that cannot be true, I mean, one pearl doesn’t make a necklace. The question is, how is a biotope defined and what, if any, is the minimum size for a biotope? Don’t panic, here’s the definition for you: “A biotope is defined as the combination of an abiotic habitat and its associated community of species. It can be defined at a variety of scales (with related corresponding degrees of similarity) and should be a regularly occurring association to justify its inclusion within a classification system”. Even better, there are ‘Criteria for defining a biotope’ one of which states: “As a working guide the biotope extends over an area at least 5 m x 5 m…” On February 10th 2013, with all that in the back of our minds, my friend Séamus Whyte and I did a casual, initial walkover in the outer Creek to see what might be there. Given the paucity of records, we weren’t necessarily expecting our first foray to strike biological gold, which was good because in fact it didn’t. That said we did find oysters on that day, and evidence of associated trawling (Figure 1). It was only once we got right down to low water, where the sediment was more mixed, that we started to see some O. edulis (Plate 1, Figure 1). Other mollusc's were also present, sharing the same habitat, including slipper limpets, Crepidula fornicata, (Plate 1 in Figure 1). In addition there were a few live Pacific oyster, Magallana gigas, higher up on the shore, around the mid-tide level and below (Plate 2, Figure 1). We also came across a small winter-weathered patch of dwarf Zostera not far from the solitary Pacific oyster marked on Figure 1. In one area at low water a number of O. edulis were seen, hinting at a potential bed, but on that first day it was enough to know there were some oysters present. And those dredge scars? They could be interpreted as reinforcing the idea that the area contained shellfish in quantities significant enough for some local, commercial fisherman to deploy their gear (Plate 3, Figure 1). Our second survey took place on the evening of the 26th May 2013. For this survey we borrowed a method outlined by MarClim, a 4 year consortium project to study marine biodiversity and climate change. Not because we were including climate change in our approach, just that the method provided a useful structure with which to harvest data. Specifically, we carried out five, 3 minute searches, at two locations in the upper creek. A modest task that yielded significantly more than ‘8 species records from 5 geo-referenced photos’ and, I suspect, would have made absolutely no difference to the final decision to swing the axe (Figure 2)! Conversely, however, from this small information seed, you might, with a little sprinkle of creativity, if you wanted, heatmap an argument, sketch a possible future, from an imagined past. But first, the results! Earlier in the year I had found O. edulis to be present on the shore below a pipe and corresponding channel linked to one of the saline ponds on the Cams Estate golf course. This was the initial planned focal point of the second survey and from this a second site was identified further upstream where Fareham Lake bends sharply eastwards. In my first 3 minute walk, my path took me past 21 oysters. The length, from hinge to lip, and the width, of each oyster found during the survey was measured and recorded before they were returned to the same location where they had been encountered. The numbers were unexpected, with a total of 61 from the Pipe Shore and 41 from the Bend Shore (Plate 1, Figure 2). Using a Garmin GPS unit I tracked each of the five, 3 minute searches I did. Then in QGIS I drew a polygon around the area covered. It’s worth noting that on the final 3-minute search I only picked up 1 oyster. The applied polygon had an area value of 229 metres squared. So, whichever definition you choose, OSPAR or biotope, a lot more than 61 specimens would have been required to earn the status of ‘Oyster Bed’. This appears, on first pass, one of those results you wish was different. But let's park the 'oyster bed' construct for now, give ourselves some latitude, and think about what else we might infer from the data. To investigate the broader size distribution of the upper Fareham Creek oyster population the measurements from the Pipe and Bend Shores were combined and the normal distribution plotted (Figure 3). What does this tell us? Well, it’s very clear that the most populous size classes are those between 6 and 7 cm in length. This is interesting because it provides an indication of the age structure. Richardson et al. (1993) used acetate peels of umbo growth lines to determination the age and growth rate of the European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis, in British waters. Their study included Solent oysters which they reported were able to grow to 6cm in 5 years. Kamphausen (2012) was also very instructive. She notes that Vanstaen and Palmer (2010) indicate that, 'oysters of this population [Ryde Middle] are expected to grow to the minimum landing size of 70 mm in 4 to 5 years'. Kamphausen's size range varied from 3.5cm – 8cm and from this she estimated that her oysters were 4 to 6 years old. But she also notes that, 'due to ecomorphological variability the exact age of an oyster cannot simply be inferred from size'. This ecomorphological variability can, I think, be glimpsed in our data. Principally, in the scatter plot of length / width measurements of the specimens sampled (Figure 4). Note the spread of points about the linear trendline with its R-squared value of 0.646. That value is not bad and certainly indicates a moderate degree of correlation between the two variables. That said there is still a substantial amount of unexplained variability or ‘random’ variation in the measurements that is not captured by the linear regression model. In ecological terms I’d be surprised if that variability wasn’t present. O. edulis are oval in shape but each animal will have experienced slightly different environmental conditions depending on where it settled, what it settled on, what biological and physical interactions it had been subjected to etc. As such we might interpret this as is a small window on the ecomorphological variability Kamphausen talks about. Equally though, you could infer from the other-side-of-the-coin, and suggest that the conditions experience by the oysters in Fareham Creek have been ‘moderately’ uniform (with the usual caveat about the relatively small sample size and unknowns which might be confounding the results!). Interestingly, Kamphausen (2012) and Vanstaen and Palmer (2010) note that shell growth in wild populations is rapid in the first 4 to 5 years but slows down appreciably from the fifth year onwards. They found most oysters to be 2 to 6 years old with only 1-2% representing the older age classes up to 14 years old. This suggests that specimens larger than 6 or 7cm may be significantly older than those in the smaller size classes. The single largest oyster I found on the Pipe Shore, Fareham Creek was 8.8cm whilst that from the Bend Shore was 9cm. The age of these can only be guessed at. However, most specimens were 6 - 7cm which based on the published evidence puts them roughly, at about 5 years old. What else might we find? For example, that bell curve in the plot appears to be showing a population, with respect to size class, that is normally distributed (Figure 3). Can we infer anything reliably from such a plot? Maybe not. But again, let’s not close the door completely, thoughts and more importantly questions, can still float in on this tide. Listen close with me for a little longer. What whispers from the oysters of Fareham Creek can we hear? Remember though and beware, whispers and data can deceive (what if our data set had a temporal envelope, instead of being a single snapshot, and covered a wider physical extent, would the picture look different?):

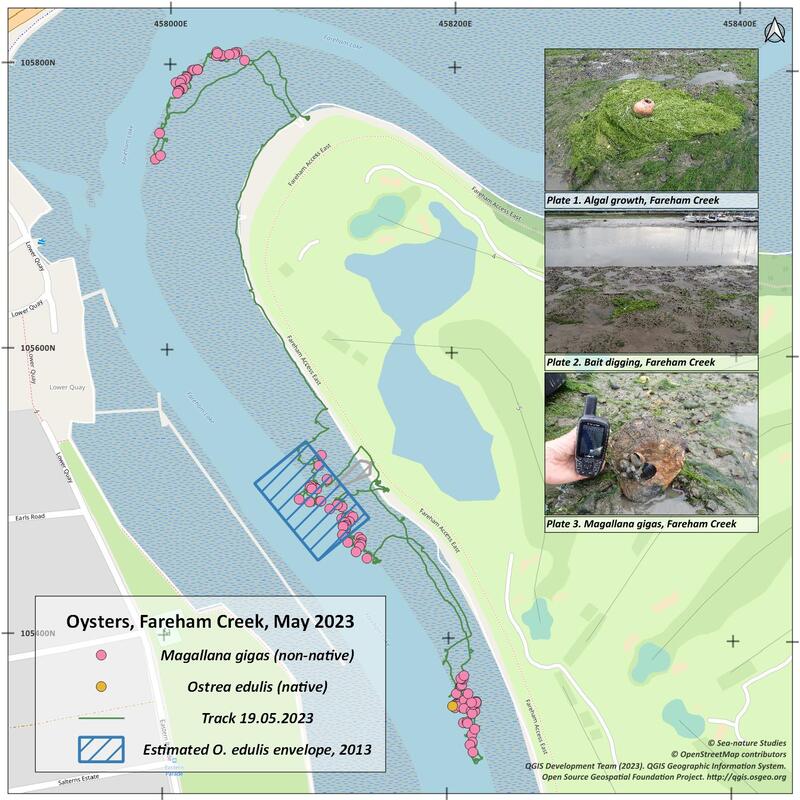

What if this habitat, evidently rich in some respects, has never had populations of native oysters which could be characterised as ‘Beds’? What if it’s natural state either in the past, or at least, most certainly now – the ‘now’ of 2013 – is of a string, or ribbon, let’s call them ‘Oyster Ribbons’, straddling the channel at low water and extending up and down the estuary for hundreds of meters? What if the term ‘Oyster Bed’, just isn’t the right one to apply? Once imagined, it takes root, and I confess I’ve mentioned my idea of ‘Oyster Ribbons’ to various people over the years and in all honesty I have to say, it has had zero traction. But it appeals to the poet in me, as well as the biologist, so you see, it’s hard to let go and yes, I appreciate it could be because it has no basis in reality (thanks so much for mentioning that). But equally, silence, to a proposed idea, is not a terribly persuasive counter-argument. Figure 5 is therefore my attempt to visualise my oyster ribbons using the heatmap function in QGIS and basing the predicted heatmap on the actual data gleaned from the timed-searches and, extrapolating from there. Ten years pass. It’s the evening of the 19th of May 2023. What will we find? How have the oysters faired in the intervening years? Read on, but don’t lose heart (Figure 6). Ostrea edulis, except for a single small specimen, is entirely absent. If there ever were collectives, such things as oyster ribbons, they are not there now. There are monstrous accumulations of ephemeral green algae blanketing the shore. It was present in 2013, just not anywhere near to the same extent as seen this time. Does clean water, unburdened with excess nutrients from agricultural run-off and the routine discharge of effluent from CSOs [Combined Sewer Overflows], power such growth? It does not. Without waiting for an answer, we have asked our Creek to shoulder these discharges and deliver them to the sea, turning rich mixed muddy gravels dark beneath this proliferating green. The algae is a small part of the habitat which has been handed a feast, breaking the natural limits which normally circumscribe its presence. Unlike us it can't say no to such things, it can only respond to the new conditions, while we look on wondering, 'Gosh, what's happening, who's done this?'. But an equal horror is the physical damage. I had seen it over the years. Commercial bait diggers mercilessly shoveling the sediment again and again. Prohibitions ignored and utterly unenforced. Even while I was there on May 19th there was a bait digger working over, an area already worked over. The location? The Pipe Shore. Relentless. If you’re not looking for it, O. edulis would be easy to miss. How many were trodden deep into the sediment? How many buried beneath spadefuls of dug material? Pummeled, broken, gone. You can’t grow a forest in ploughed fields. And the shell. The shell of a number of species, which littered the shore in 2013 has all but evaporated. Winnowed out and not replaced. There is still shell present but it's insubstantial. You'd find more corporeal presence in a ghost or a memory. But lost from the system, or just not replenished? The latter would argue that bivalve mollusc's more generally have been lost. This would fit with evidence unearthed by the Environment Agency during their long investigation into Southern Water. Perhaps it is not just the oysters which have been disrupted, perhaps it's not just bait that's been cut? Does this, in part, explain the loss of shell material from the ravaged sediments? I know, such emotional language, but sometimes nothing else will do. People have to mourn. How do Pacific oysters survive the war? Well, visually they are hard to miss with their waved edge and contrasting colour-patterns. Of course, they also grow fast and are adaptable to a range of environmental conditions. Plus, they’re bigger and sharp looking, so perhaps have more chance of being avoided and growing to maturity? If you’re looking for a rant against the Pacific oyster this page will disappoint you. Each time my hyperbole alarm goes off, as words such as 'invasive' are deployed, I ask myself this, 'are they really the enemy?'. How easily we forget that correlation is not causation when the ground beneath our feet slopes more strongly. How quickly we neglect other possible hypotheses when the axiomatic account pushes its pillow down, muffling our brain. The lure of simplicity with its sweet economy. The answer is sooo obvious! The native oyster is gone, the Pacific oyster is here. The solution? Wipe out the invader! Beware of such lazy parsimony. Fear it for the enemy it is, muzzle your inner vandal, challenge the call to cull, the pleasure would be fleeting, the damage not. Questions can often defuse (or failing that a good run!). Do I really have the evidence to justify such action?' Violent, destructive behaviour almost inevitably serves, explicitly or implicitly other agendas, very rarely ourselves or our local ecology. Ask yourself too, for example, what ecosystem services currently being degraded or lost, might be, to some degree, replaced by the presence of this new oyster? Is this species undermining the resilience of the faunal communities here or functionally supporting them (or a combination of the two)? O. edulis likes to settle on shell, this is why some efforts to boost its population seed receiving waters with old shell from sources where previously such material would have been thrown out as waste. But O. edulis do not only settle on other O. edulis. In fact, it's been noted by some researchers in Scandanavia that they can also settle on, you guessed it, Pacific oyster. To what extent? Good question. We don't know because these kinds of questions are made dormant by our prejudice. The narrative laid out here is not exhaustive. Other speculative interpretations or inferences could be suggested for the observed results, other questions asked. O. edulis populations in the wider area have suffered in the past. In light of that how important might these upper creek populations be? Have they always persisted in such areas or did they re-populate? What would a survey in 2003 recorded? Or in 2018? The data set is not large but it does mark this, O. edulis was present in 2013 and a decade later, it is absent. I must now ask you to believe that this brief report is not a council of despair. That all this is not a reprimand. I see a different future. I see a return of native oysters to Fareham Creek, perhaps even a manifestation of oyster ribbons. Who knows. All it takes is collective better behaviour, from all of us, to change the underlying conditions. It is possible, but only if we work for it and don't accept the degradation we've created. Bait industry, you could take the lead, and show some reform. You can't continue to sell bait to fisherman if the fish move away because we've ripped holes in the food-web which previously enabled their proliferation. Least we forget, here's a quote you'll be familiar with as it was covered by many news outlets, this was from the Guardian, 9th July 2021: "Mr Justice Johnson said the company [Southern Water], which was fined £90m, had discharged between 16bn and 21bn litres of raw sewage into some of the most “precious and delicate ecosystems and coastlines” with a disregard “for human health, and for fisheries and other legitimate businesses that operate in the coastal waters”. Now Southern Water is partway through 'investing £2 billion'. But as they say, the proof of the pudding is in the eating and given the track record? Well, you could be forgiven for harbouring some dispondency. All of us remember this. I am part of the problem. I have witnessed the decline and not raised my hand. So I ask this of myself and of you: Be mad, but for pity's sake, be careful what you're mad about; and, "... be kind, while there is still time". Our collective inaction has created this and our peaceful, sustained, collective action and engagement can change it. What can we do? Wear a ribbon (of any colour) for the oysters of Fareham Creek #OysterRibbons. Change the bait you use; change the way you fish; dig your own; don't dig more than you really need, back fill your holes and rotate your effort letting over-worked locations lie fallow; or, dig more naturally disturbed, exposed shores. These things are known, they just need to be done. If industry shows no care it's up to us to show them the way. Write to your Fareham Councillor and say, 'We want Fareham Creek to have it's oysters back, we want it unchoked by algae, with healthy, undisturbed and gloriously shelly, muddy gravel; and, we want you to help bring this about. In ten years time the picture can begin to be reversed, if we start today'! But I'm sure we can do even more. We can all be stewards and promote a declaration, our own designation that says this is our creek, our Wild Site and, we stand with it. References

Connor, D.W., J.H. Allen, N. Golding, K.L. Howell, L.M. Lieberknecht, K.O. Northen and J.B. Reker (2004). The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland Version 04.05. ISBN 1 861 07561 8. Available from https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/resources Kamphausen, L. M. (2012). The reproductive processes of a wild population of the European at oyster Ostrea edulis in the Solent, UK. PhD Thesis. Faculty of Natural and Environmental Sciences. School of Ocean and Earth Science Richardson, C. A., Collis, S. A., Ekaratne, K., Dare, P., & Key, D. (1993). The age determination and growth rate of the European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis, in British waters determined from acetate peels of umbo growth lines. ICES Journal ofMarine Science, 50(4), 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsc.1993.1052. Vanstaen, K. and D. Palmer (2010). Solent Regulated Fishery Oyster Stock Survey 15 - 21 June 2010. Technical report. Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science, Lowestoft Laboratory. 31 p.

2 Comments

|

|

© Copyright 2017 Peter Barfield, All rights reserved in all media.

Copyright applies for all images, video and texts so please contact me for permission to use. |

Website by Ericaceous

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed