UPDATE - January 2022

The 7th Quinquennial Review (QQR 7) process has been underway since April last year and the penultimate stage, the stakeholder consultation, is due to close at 23:59 on Sunday 30 January 2022. There is then a final stage, 'Peer review and sign off'.

If you've read the article I wrote in 2016, you might be wondering what the much delayed QQR7 has to say about Nematostella vectensis. The answer is that the JNCC are recommending to remove the species from protection under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. The 'Recommendation rationale' provided in the spreadsheet is succinct, 'non-native'. The take-home message being that the Starlet sea anemone does not meet the eligibility criteria for non-native species, unsurprising given the case laid out below.

A total of 8 species in QQR7 have the same recommendation for the same reason, three animals and five plants. The other two animals are, Natator depressus (Flatback turtle) and, Victorella pavida (Trembling sea mat).

It's worth noting that as part of QQR6 it was recognised that, "The phrase “place of shelter or protection”, has long caused difficulties for the QQR process. Previous QQRs have been rather inconsistent in their interpretation of what is meant by this phrase, and as a consequence some of the species now listed on Schedule 5 and 8 are there only because their habitat needs to be protected".

Those interested in what the recommendations are for all of the species concerned can find a spreadsheet with outline details from DEFRA, here (while it's available).

If you've read the article I wrote in 2016, you might be wondering what the much delayed QQR7 has to say about Nematostella vectensis. The answer is that the JNCC are recommending to remove the species from protection under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. The 'Recommendation rationale' provided in the spreadsheet is succinct, 'non-native'. The take-home message being that the Starlet sea anemone does not meet the eligibility criteria for non-native species, unsurprising given the case laid out below.

A total of 8 species in QQR7 have the same recommendation for the same reason, three animals and five plants. The other two animals are, Natator depressus (Flatback turtle) and, Victorella pavida (Trembling sea mat).

It's worth noting that as part of QQR6 it was recognised that, "The phrase “place of shelter or protection”, has long caused difficulties for the QQR process. Previous QQRs have been rather inconsistent in their interpretation of what is meant by this phrase, and as a consequence some of the species now listed on Schedule 5 and 8 are there only because their habitat needs to be protected".

Those interested in what the recommendations are for all of the species concerned can find a spreadsheet with outline details from DEFRA, here (while it's available).

The UK non-native species Nematostella vectensis (starlet sea anemone).

I should probably begin by saying that this article may be redundant. In one sense it certainly is because key aspects of the case I'll describe here have already been detailed in a paper published in 2008. No action based on this work has been made publicly available and in fact the paper itself suggested in part that this might be an appropriate response. But it's likely that, behind the scenes, this has been chewed over and, it could be, actions are in process and in due course these will be made public.

The paper in question is Reitzel et al. (2008) but in fact, as is often the case, the story really begins before that, with Sheader et al. (1997). Sheader et al. (1997) were the first to suggest that Nematostella vectensis might be an introduced species. These authors did not use the term ‘non-native species’ directly but they do clearly indicate that this may be the case and suggest that a genetic study of existing populations should be undertaken to clarify the situation. Eleven years pass before a study is published which uses DNA fingerprinting from hundreds of individuals collected from 24 different locations including, of course, the UK. In 2008, Reitzel et al. make the following definitive statement:

'Collectively, these data clearly imply that N. vectensis is native to the Atlantic coast of North America and that populations along the Pacific coast and in England are cases of successful introduction'.

That's about as unequivocal as good science gets. For our story here it's worth noting that Reitzel et al. (2008) clearly identify that the, 'conservation of introduced N. vectensis populations in England appears to be motivated by its misidentification as a native species'.

So, we have a Schedule 5 protected species under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (herein abbreviated to WCA 81) which is in all likelihood a non-native species. Not necessarily a problem because in fact, there are mechanisms in place which allow non-native species to be listed. In their concluding remarks Reitzel et al. (2008) suggest that N. vectensis, 'populations continue to receive modest protection, with the understanding that such protection is serving the more general goal of protecting a threatened habitat'. I take their point entirely but those sensitive / threatened habitats are themselves already directly protected by current legislation. Strengthening that shield by identifying any associated individual species which require protection measures is reasonable, provided that such additions are legitimate within the legal framework or, supported by it. But, should a species be captured by existing legislation if, in doing so, it brings into disrepute the very mechanism by which that protection is achieved? Obviously, I am not privy to what the authors may have intended but as a strong and fundamental piece of legislation for the protection of species in the UK, the WCA 81 is unlikely to have ever been described as modest.

Could N. vectensis remain, or be re-listed on Schedule 5, given its status as a non-native species?

The Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), review Schedules 5 and 8 of the WCA 81 every five years in a process called the Quinquennial Review (QQR). In April 2014, the Sixth Quinquennial Review was submitted to Defra, the Welsh Government and the Scottish Government. These governments have subsequently been considering the review and will, in due course, 'respond formally and publish amendments to the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981)' (JNCC 2015).

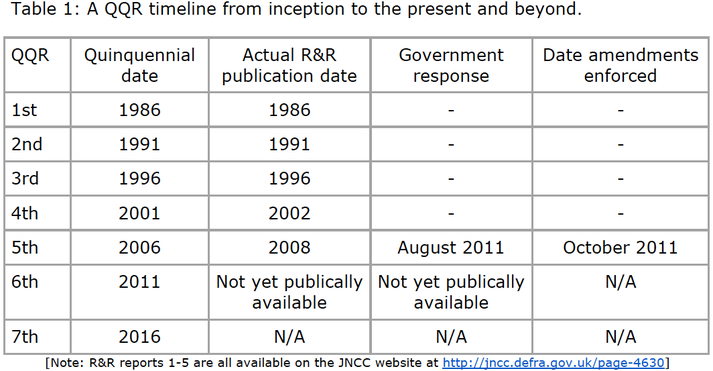

Predictably, the first QQR 'report and recommendations' (R&R) document was published in October 1986 (NCC 1986). Following the 'quinquennial' requirement it is possible to construct a timeline from subsequent publications (Table 1).

The paper in question is Reitzel et al. (2008) but in fact, as is often the case, the story really begins before that, with Sheader et al. (1997). Sheader et al. (1997) were the first to suggest that Nematostella vectensis might be an introduced species. These authors did not use the term ‘non-native species’ directly but they do clearly indicate that this may be the case and suggest that a genetic study of existing populations should be undertaken to clarify the situation. Eleven years pass before a study is published which uses DNA fingerprinting from hundreds of individuals collected from 24 different locations including, of course, the UK. In 2008, Reitzel et al. make the following definitive statement:

'Collectively, these data clearly imply that N. vectensis is native to the Atlantic coast of North America and that populations along the Pacific coast and in England are cases of successful introduction'.

That's about as unequivocal as good science gets. For our story here it's worth noting that Reitzel et al. (2008) clearly identify that the, 'conservation of introduced N. vectensis populations in England appears to be motivated by its misidentification as a native species'.

So, we have a Schedule 5 protected species under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (herein abbreviated to WCA 81) which is in all likelihood a non-native species. Not necessarily a problem because in fact, there are mechanisms in place which allow non-native species to be listed. In their concluding remarks Reitzel et al. (2008) suggest that N. vectensis, 'populations continue to receive modest protection, with the understanding that such protection is serving the more general goal of protecting a threatened habitat'. I take their point entirely but those sensitive / threatened habitats are themselves already directly protected by current legislation. Strengthening that shield by identifying any associated individual species which require protection measures is reasonable, provided that such additions are legitimate within the legal framework or, supported by it. But, should a species be captured by existing legislation if, in doing so, it brings into disrepute the very mechanism by which that protection is achieved? Obviously, I am not privy to what the authors may have intended but as a strong and fundamental piece of legislation for the protection of species in the UK, the WCA 81 is unlikely to have ever been described as modest.

Could N. vectensis remain, or be re-listed on Schedule 5, given its status as a non-native species?

The Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), review Schedules 5 and 8 of the WCA 81 every five years in a process called the Quinquennial Review (QQR). In April 2014, the Sixth Quinquennial Review was submitted to Defra, the Welsh Government and the Scottish Government. These governments have subsequently been considering the review and will, in due course, 'respond formally and publish amendments to the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981)' (JNCC 2015).

Predictably, the first QQR 'report and recommendations' (R&R) document was published in October 1986 (NCC 1986). Following the 'quinquennial' requirement it is possible to construct a timeline from subsequent publications (Table 1).

The eligibility criteria for a species to be listed on Schedules 5 (or 8) of the WCA 81 are clearly laid out in the QQR 6 information pack (JNCC 2012). The single eligibility criterion for non-native species is stated as follows:

'i. Generally, only native (including reintroduced native) taxa are to be considered (See Part 3.4.1 A). In exceptional circumstances, non-native taxa which have been introduced or thought to have been introduced to Great Britain by man could be considered if the species is endangered or extinct in its native range and if current information suggests that the species is unlikely to have an adverse impact on UK native species'

Even if the species passes this test it is then subjected to the following condition:

'preference will be given to those non-native species whose native range reaches the north west coast of Europe (i.e. continental distribution extends to the Atlantic coast of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany or Scandinavia) and for marine taxa, the distribution includes the north west Atlantic area'.

The first test is clear. The species must be endangered or extinct in its native range. But how is 'endangered' defined in this context? This is clarified by the JNCC (2012). A species is considered endangered when either of the following is true:

- it is included in a JNCC-approved British Red List http://jncc.gov.uk/page-3352, using the revised IUCN criteria, as Extinct in the Wild, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable;

- records indicate that the species is known from only a single locality or severely fragmented

In publishing the red list status in their taxon designations spreadsheet (available online at http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-3408) the JNCC have endorsed the assessment of 'vulnerable' for N. vectensis. One of the quality checks adhered to by the JNCC is that the version used is the 2001 IUCN version 3.1 (or later). But the assessment for N. vectensis is based on 'ver 1994; A1ce', or version 2.3. Although the assessment is based on pre-2001 criteria, rather than the 'revised' criteria referred to above, this clearly passes the hurdle for accepting that the species is 'endangered'.

The global assessment of 'Vulnerable - (V)', which has been in place for the species since 1983, is defined as follows based on the 1994 description (IUCN 2015):

'Taxa believed likely to move into the 'Endangered' category in the near future if the causal factors continue operating. Included are taxa of which most or all the populations are decreasing because of over-exploitation, extensive destruction of habitat or other environmental disturbance; taxa with populations that have been seriously depleted and whose ultimate security has not yet been assured; and taxa with populations that are still abundant but are under threat from severe adverse factors throughout their range. N.B. In practice, 'Endangered' and 'Vulnerable' categories may include, temporarily, taxa whose populations are beginning to recover as a result of remedial action, but whose recovery is insufficient to justify their transfer to another category'.

The associated condition for acceptance of a non-native species on Schedule 5 or 8 is only half met. The native range does not extend to the 'north west coast of Europe', but is within the broader, 'north west Atlantic area'. As this condition is not strictly recorded as an 'eligibility criteria' there may be more latitude given to its application.

The notes on endangerment clearly state that this, on its own, cannot be considered sufficient justification, 'for recommending a taxon for scheduling' (JNCC 2012). It goes on to say:

'Many taxa will be endangered principally due to changes in land-use or land management leading to increased habitat fragmentation, deterioration or outright habitat loss. Such causes of endangerment do not constitute ‘direct human pressures’ as covered by Sections 9 and 13 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (and listed in Part 3.2 above). To be recommended for scheduling, the endangerment of a taxon must, at least in part, be due to one or more of the direct human pressures listed in Part 3.5'.

So, even where the eligibility criterion is met, the WCA 81 requires, 'a strong case that scheduling will afford significant benefits to it through a decrease in any of the direct human pressures listed below:

i. intentional killing or injuring, picking or uprooting or reckless disturbance; or

ii. ‘collection’ including possession, dead or alive, in full or part thereof; or

iii. intentional or reckless damage, disturbance or obstruction to any structure or place of shelter and protection which is regarded as essential for the survival of the species6 (such as nests, burrows, holes, scrapes, or similar resting sites; sites used to raise young (and eggs), holts); or

iv. currently or potentially damaging trade, or other forms of exploitation or pressure.

[6 This excludes the wider habitat in which the organism ranges]'

Let's skip back to that definition of 'Vulnerable' for a moment. Note, that it highlights 'extensive destruction of habitat or other environmental disturbance' as an important causal factor. Is there evidence in its home range that N. vectensis is exposed to this issue? Hand and Uhlinger (1992) reported the following from the key IUCN publication:

'Williams (1983) considered the species vulnerable to extinction in Great Britain, but it is plentifully abundant throughout most of its range and is readily collected'.

It is of course unsurprising that the species is also considered a UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) priority species and as such we have a report from the JNCC (2010). This report provides the following assessment with respect to 'Crit 1 Global threat' in Section 8 'Additional information from specialists' (compiled during Stage 1 of the priority species review - prior to 2007 (JNCC 2007)):

'None - it is widespread across eastern and western seaboards of U.S.A., Canada along with the few sites in south England and East Anglia'.

This updates the statement from Williams (1983), confirming the health of the species in its native range. The same report, states that for 'Crit 1' it is not, 'known if U.K. population is relict from last glaciation or introduced by human agent from U.S. However in Europe it is only known from ~20 lagoons in England and is therefore a species of European importance' (JNCC 2010).

It seems fairly clear that the JNCC 2010 report rests on supporting information supplied prior to the publication of Reitzel et al. (2008). Hence, the status of the species remains entirely supported, because in and of itself Sheader et al. (1994) and subsequent work could not exclude the possibility that the UK population was 'relict'. But Reitzel et al. (2008) is unequivocal and less open to challenge given the nature of the study.

But there is a bigger issue, under the heading 'Habitat and Ecology' Williams (1983) states the following:

'The original habitat of this anemone was probably in shallow pools of high marshes and at sides of creeks at marsh edges in estuaries and bays [..]. North American records reflect this natural distribution pattern which facilitates the spread of the species from established to developing marsh, probably by tidal and storm action sweeping anemones from pool to pool and possibly to a lesser extent by wildfowl fortuitously transporting vegetation with adhering anemones. The English distribution is atypical and is the reason for the species being endangered'.

The last sentence is absolutely critical. Williams, in 1983, is unaware that N. vectensis is not native to England, and based on the threat perceived to that population, lists the species as globally 'Vulnerable' under the IUCN criteria. Based on this evidence the UK subsequently lists the species on Schedule 5 of the WCA 81 in 1988. Reitzel et al. (2008) suggest that the conservation measures for N. vectensis in England are, 'motivated by its misidentification as a native species'. But actually the entire case for the global assessment of 'Vulnerable' rests on that misidentification as do all subsequent protection measures.

Having read this article do you believe that N. vectensis can, as currently enshrined, remain on Schedule 5 of the WCA 81? Could it reasonably retain its status as a UK BAP priority species or a Species of Principal Importance in England under the NERC Act (2006)? Or, still be listed as a Feature of Conservation Interest (FOCI) for Marine Conservation Zones?

The IUCN (2015) assessment for N. vectensis was last updated in 1996. The current assessment is tagged as 'Needs updating'. So what is the delay? Why has no action been taken? Wheels turn slowly sometimes. That’s clear. Human. Perhaps there’s a piece of the puzzle missing. Work in progress, yet to be made public. Either way an update is long overdue and once that update has been carried out, any subsequent amendments that may be required can be cascaded through the relevant statutory mechanisms in the countries affected.

As I indicated at the start, it seems clear that all of this is likely to be already well understood and in hand in one form or another. Reitzel et al., (2008) is obviously key to the analysis I’ve presented here. The statements made in the paper appear definitive to me. But it could be that more research is required. DNA fingerprinting is not my area of expertise.

If N. vectensis is a non-native species there needs to be better understanding of what the impacts to our native habitats and species from N. vectensis are / have been. Reitzel et al. (2008) suggest that the species 'is unlikely to have negative ecological consequences'. But the lens and context through which the species has been viewed has surely changed and a reassessment from funded research would not be inappropriate.

Moran and Gurevitz (2006) state that because:

'N. vectensis is exposed to a minimal variation of prey and foe, its neurotoxin gene family did not face the selective pressure that neurotoxin genes of other animals were subjected to. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that at least in some lagoons this anemone is feeding on a small variety of organisms [..]. A similar prey variety was observed in two lagoons located on different sides of the Atlantic at Nova Scotia and England, indicating that N. vectensis populations in different areas may be exposed to the same limited variety of prey, neglecting again the advantage of rapid neurotoxin evolution in a unique habitat as the brackish lagoon […]. A large number of genes encoding for the same mature neurotoxin might provide the anemone with the ability to rapidly produce a large mass of Nv1 [Nematostella vectensis neurotoxin 1] and quickly ‘reload’ its toxin reservoir. Such ability is highly beneficial in the crowded brackish lagoon, where the anemone might encounter large foe and prey populations within a short period of time'.

That sounds a little like possible competitive advantage to me.

Williams (1983) notes that the, ‘original habitat of this anemone was probably in shallow pools of high marshes and at sides of creeks at marsh edges in estuaries and bays’. Do we know for sure that the species isn’t more widely present in similar areas here in the UK? Who’s up for a muddy snorkel?

References

Hand, C. & Uhlinger, K. 1992. The culture, sexual and asexual reproduction, and growth of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Biol Bull 182:169–176.

IUCN 2015. World Conservation Monitoring Centre. 1996. Nematostella vectensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 1996: e.T14500A4440023. Downloaded on 15 December 2015.

JNCC 2007. Report on the Species and Habitat Review. Report by the Biodiversity Reporting and Information Group (BRIG) to the UK Standing Committee June 2007. Available online at: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/_ukbap/UKBAP_Species_HabitatsReview-2007.pdf - last accessed December 2015.

JNCC 2010. UK Priority Species data collation Nematostella vectensis version 2 updated on 15/12/2010. Available online at: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/_speciespages/471.pdf - last accessed December 2015.

JNCC 2012. 6th QUINQUENNIAL REVIEW. The Information Pack. July 2012. Available online at: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/pdf/QQR6_informationpack_2012.pdf - last accessed December 2015.

JNCC 2015. Sixth Quinquennial Review. Available online at: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-6194 - last accessed December 2015.

Moran, Y. & Gurevitz, M. 2006. When positive selection of neurotoxin genes is missing. The riddle of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. FEBS Journal 273 (2006) 3886–3892. DOI:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05397.x

NCC 1986. Nature Conservancy Council. Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981. First Quinquennial Review of Schedules 5 and 8. Background paper and submission of recommendations. Available online at: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/pdf/1qr.pdf - last accessed December 2015.

Reitzel, A.M., Darling, J.A., Sullivan, J.C. and Finnerty, J.R. 2008. Global population genetic structure of the starlet anemone Nematostella vectensis: multiple introductions and implications for conservation policy. Biological Invasions. 10(8): 1197 -1213.

Sheader, M., Suwailem, A.M. and Rowe, G.A. 1997. The anemone, Nematostella vectensis, in Britain: considerations for conservation management. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 7: 13-25.

Williams, R. B. 1983. Starlet sea anemone: Nematostella vectensis. Pp. 43-46 in The IUCN Invertebrate Red Data Book. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Citation: This article was originally published in the Spring 2016 edition of the Bulletin of the Porcupine Marine Natural History Society and can be cited as follows:

Barfield, P. D. (2016). The UK non-native species Nematostella vectensis (starlet sea anemone). Bulletin of the Porcupine Marine Natural History Society, No. 5, 33-37. ISSN 2054-7137.

© Sea-nature Studies, 2016. All rights reserved in all media.

| pmnhsbull5_uknnsnv.pdf |