Notes on the immigrant, Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne-Edwards, 1853), in the Mediterranean.

In the summer of 2007 I went to Sicily for the first time. For part of the time I was there I stayed on the Aeolian island of Salina. The Aeolian islands are just off the north-east coast of Sicily in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It was beautiful and hot and I spent a fair amount of time in the water keeping cool and snorkelling to my heart’s content. Bliss, apart from head-butting a small Pelagia noctiluca.

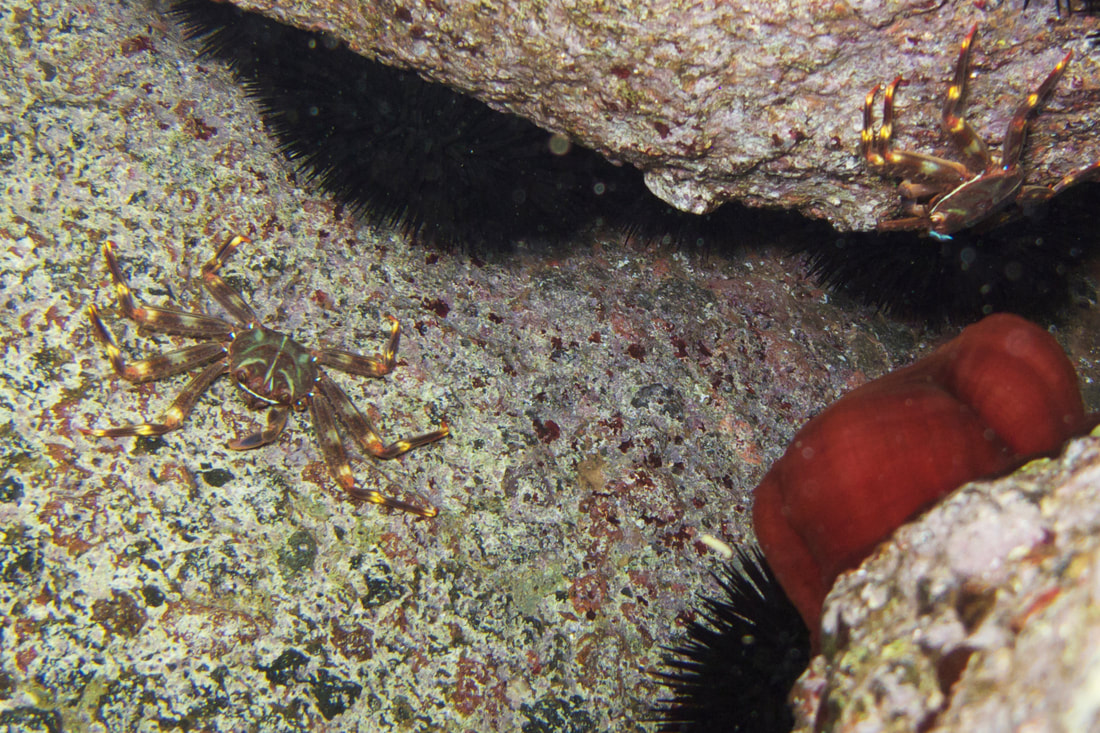

Anyway, on my first snorkel the most obvious animal I saw was a long-legged, nimble-footed crab with highly distinctive yellow bands on its legs. These colourful and extremely flat crabs were scuttling under practically every rock I floated over. I watched one rapidly tugging algae from the rock with its chelae until it realised something was up and slipped from view.

Anyway, on my first snorkel the most obvious animal I saw was a long-legged, nimble-footed crab with highly distinctive yellow bands on its legs. These colourful and extremely flat crabs were scuttling under practically every rock I floated over. I watched one rapidly tugging algae from the rock with its chelae until it realised something was up and slipped from view.

Being almost entirely ignorant of conspicuous Mediterranean fauna I had no idea what species of crab I was looking at. So later on that day I consulted my copy of the Hamlyn Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the Mediterranean Sea (1982). To my surprise, given the large numbers I had seen on a short snorkel it was not in the book. But hey it’s an old book and maybe I needed something a little more decapod-specific. The other thought was that perhaps it was a non-native species. This second thought was more interesting so that was what I googled around when I got back to the UK.

Percnon gibbesi, the Sally Lightfoot crab, was first recorded in the Mediterranean in the summer of 1999 at Linosa (Cannicci et al. 2006, Puccio et al. 2006). Linosa is one of the three Pelagie Islands in the Sicily Strait south of Sicily, about half way to Tunisia. At around the same time it was also found from the Balearic Islands off the south-east coast of Spain (Yokes and Galil 2006). This eurythermal, subtropical, subtidal, grapsid crab is now widely distributed in the Mediterranean (Zaouali et al. 2007, Deudero et al. 2005). The crab’s native distribution extends from Chile to California, from Florida to Brazil and from the Gulf of Guinea to the Azores (Cannicci et al. 2006, Galil et al. 2006).

Percnon gibbesi, the Sally Lightfoot crab, was first recorded in the Mediterranean in the summer of 1999 at Linosa (Cannicci et al. 2006, Puccio et al. 2006). Linosa is one of the three Pelagie Islands in the Sicily Strait south of Sicily, about half way to Tunisia. At around the same time it was also found from the Balearic Islands off the south-east coast of Spain (Yokes and Galil 2006). This eurythermal, subtropical, subtidal, grapsid crab is now widely distributed in the Mediterranean (Zaouali et al. 2007, Deudero et al. 2005). The crab’s native distribution extends from Chile to California, from Florida to Brazil and from the Gulf of Guinea to the Azores (Cannicci et al. 2006, Galil et al. 2006).

The crab lives in narrow rocky subtidal zones in the upper infralittoral, commonly in depths of 1-2m (Yokes and Galil 2006). It greatly favours boulders both for their micro-algal turf and the protection offered beneath (note to the naked eye, the boulders appear largely, to lack any macro-algae and macro-benthic colonies, pers. obs., Deudero et al. 2005, Pipitone et al. 2001).

Barriere di scogli (jumbles of rock and concrete blocks placed along the coast as sea defence barriers) and pennelli (similar in function to our groynes) constructed from the same material seemed to be a common sight in Sicily. It was around one such barriere di scogli structure that my first snorkel took me. Unsurprisingly, Percnon gibbesi found such man-made structures as these and harbour breakwaters perfect places to colonise (Yokes and Galil 2006).

Barriere di scogli (jumbles of rock and concrete blocks placed along the coast as sea defence barriers) and pennelli (similar in function to our groynes) constructed from the same material seemed to be a common sight in Sicily. It was around one such barriere di scogli structure that my first snorkel took me. Unsurprisingly, Percnon gibbesi found such man-made structures as these and harbour breakwaters perfect places to colonise (Yokes and Galil 2006).

In a Mallorcan report Deudero et al. (2005) found the most frequent carapace length (CL) to be between 21-25mm but ranged from 5-40mm. The sex ratio was 2 males for every 3 females and one location might have between 2-14 individuals. The depth range Percnon gibbesi was found to inhabit varied from 0-4m but the majority (84%) were found in 0-2m. In this study none were found below 8m and the larger crabs (with a CL over 10mm) tended to be found in deeper water (3-4m) than the smaller crabs (<1m). Unsurprisingly Sally Lightfoots are vulnerable to predation by fish and other invertebrates.

On another snorkel just west of the lighthouse near Lingua on Salina, around sunset, I saw many more Sally Lightfoots and they seemed less wary. According to Deudero et al. (2005) activity of this species is highest at sunset.

Analysis of stomach contents suggest that Percnon gibbesi is a strict herbivore (Puccio et al. 2006). This makes it unique among the other large-sized infralittoral Mediterranean crab. So an abundance of food and a lack of decapod competitors can be added to the list of why this grapsid crab is doing so well in it’s new home. Of course, other grazers in the upper infralittoral may be in competition with it. Puccio et al. (2006) mention two important grazers in this area, the sea urchins Paracentrotus lividus (de Lamarck, 1816) and the black urchin, Arbacia lixula (Linnaeus, 1758).

It should be noted however that Deudero et al. (2005) observed that food selection appeared opportunistic with algae as well as pagurids and polychaetes taken. Although Puccio et al. (2006) argued that given the scarce occurrence of such items in the stomach they were not being specifically chosen. He backed up this analysis showing the chelae to be shaped like those of vascular plant eaters. In addition the gastric mill (part of the digestive tract of crustaceans) contained structures which corresponded to those found in grazers not predators.

The consensus of opinion on how Percnon gibbesi entered and spread in the Mediterranean seems to be that it was introduced through surface currents and then had its dispersal accelerated by ship borne transport (Yokes and Galil 2006, Pipitone et al. 2001, Galil et al. 2002). It’s likely that Percnon gibbesi came through the Strait of Gibraltar as the population in the Mediterranean shares similar morphological characteristics with those found in the Atlantic (Pipitone et al. 2001).

Conversely Abello et al. (2003) suggested its larvae entered with Atlantic currents and then dispersed naturally, However although the crab has a long larval lifespan of up to 6 weeks, data in support of a coastal transport mechanism able to explain its rapid spread is limited (Yokes and Galil 2006). However, no studies have been done to investigate its ability to export larvae over open water (Yokes and Galil 2006).

But Zaouali et al. (2007) argue the spread has, at the very least, been aided by ship transportation stating quite strongly that, “this vessel-transported plagusiid is the single most invasive decapod species in the sea, spreading within a few years from the Balearic Islands to Turkey, possibly via recreational and fishing vessels”.

Because the crab colonises breakwaters and the like with such zeal this propensity may enhance its chance of spread by ship. Its choice of creviculous habitats (Cannicci et al. 2006) and, that just a few ovigerous females might be enough to establish a viable population, may also enable the success of this form of dispersal (Yokes and Galil 2006). Puccio et al. (2006) indicate Percnon gibbesi to be a highly fecund species.

While ship borne dispersal of Percnon gibbesi may well be significant in the story of its spread through the Mediterranean it should be remember that natural dispersal will also account for some of its distribution. Thessalou-Legaki et al. (2006) in a study of the Sally Lightfoot in Greek waters notes that while shipping is a possible vector the larvae may also have rode currents across the Ionian Sea. The locations inhabited by Percnon gibbesi on the Hellenic Arch indicate this is a reasonable assumption. They go onto to suggest that it’s presence and algivorous feeding habit in the oligotrophic environment here may prove advantageous.

The larvae of Percnon gibbesi play another role in its phenomenal success in the Mediterranean (Puccio et al. 2006). It produces a very large megalopa and consequently a robust first crab (Paula and Hartnoll, 1989).

Needless to say, Percnon gibbesi is now considered “established” by CIESM (the Mediterranean Science Commission). This means that there are published records of them from at least two different localities (or in different periods), evidence which indicates the population is self-maintaining.

The impact of this new and significant presence in the infralittoral of the Mediterranean on either higher or lower trophic levels has yet to be investigated.

References:

Abelló, P., Visauta, E., Bucci, A. & Demestre, M., 2003. Noves dades sobre l’expansió del cranc Percnon gibbesi (Brachyura: Grapsidae: Plagusiinae) a la Mediterrània occidental. Bolleti de la Societat d’Historia Natural de les Balears, 46, 73–77.

Cannicci, S., Garcia, L. and Galil, B. S., 2006. Racing across the Mediterranean – first record of Percnon gibbesi (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) in Greece. JMBA2 - Biodiversity Records. Published on-line at: www.mba.ac.uk/jmba/pdf/5300.pdf

Cambell, A. C., 1982. The Hamlyn Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the Mediterranean Sea. Hamlyn 320p.

CIESM (the Mediterranean Science Commission)

The CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species is the first attempt to provide a comprehensive, group by group, survey of recent marine "immigrants" in the Mediterranean, which is undergoing drastic and rapid changes to its biota. Go online to:

http://www.ciesm.org/online/atlas/index.htm

Deudero S., Frau A., Cerda M., Hampel H., 2005. Distribution and densities of the decapod crab Percnon gibbesi, and invasive Grapsidae, in western Mediterranean waters. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 285: 151-156

Galil, B. S., Froglia, C. and Noël, P., 2006. CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean. Vol. 2. Crustaceans: decapods and stomatopods, Check-list of exotic species. http://www.ciesm.org/atlas/appendix2.html.

Galil B, Froglia C and Noel P., 2002. Vol. 2. Crustaceans: decapods and stomatopods. In: Briand F (ed) CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean. CIESM Publishers, Monaco, 192 p

Paula J and Hartnoll R. G., 1989. The larval and post-larval development of Percnon gibbesi (Crustacea, Brachyura, Grapsidae) and the identity of the larval genus Pluteocaris. Journal of Zoology London 218: 17-37

Pipitone, C., Badalamenti, F. and Sparrow, A., 2001. Contribution to the knowledge of Percnon gibbesi (Decapoda, Grapsidae), an exotic species spreading rapidly in Sicilian waters. Crustaceana 74(10): 1009-1017

Puccio V., Relini M., Azzurro E., Orsi Relini L., 2006. Feeding habits of Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) in the Sicily Strait. Hydrobiologia, 557: 79-84.

Thessalou-Legaki, M., Zenetos, A., Kambouroglou, V., Corsini-Foka, M., Kouraklis, P., Dounas, C. and Nicolaidou, A., 2006. The establishment of the invasive crab Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) in Greek waters. Aquatic Invasions, Volume 1, Issue 3: 133-136

Yokes, B. and Galil, B. S., 2006. Touchdown - first record of Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) from the Levantine coast. Aquatic Invasions, Volume 1, Issue 3: 130-132

Zaouali, J., Souissi, J ben, Galil, B. S., d’Udekem d’Acoz, C., and Abdallah, A ben, 2007. Grapsoid crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) new to the Sirte Basin, southern Mediterranean Sea—the roles of vessel traffic and climate change. JMBA2 - Biodiversity Records. Published on-line at: www.mba.ac.uk/jmba/pdf/5770.pdf

Peter Barfield (November 2007)

Citation: This article was originally published in the Winter 2007 edition of the Porcupine Marine Natural History Society Newsletter and can be cited as follows:

Barfield, P. D. (2007). Notes on the immigrant, Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne-Edwards, 1853), in the Mediterranean. Porcupine Marine Natural History Society Newsletter, No. 23, 16-17. ISSN 1466-0369.

Note: All images presented here were taken in subsequent years.

© Sea-nature Studies, 2007. All rights reserved in all media.

On another snorkel just west of the lighthouse near Lingua on Salina, around sunset, I saw many more Sally Lightfoots and they seemed less wary. According to Deudero et al. (2005) activity of this species is highest at sunset.

Analysis of stomach contents suggest that Percnon gibbesi is a strict herbivore (Puccio et al. 2006). This makes it unique among the other large-sized infralittoral Mediterranean crab. So an abundance of food and a lack of decapod competitors can be added to the list of why this grapsid crab is doing so well in it’s new home. Of course, other grazers in the upper infralittoral may be in competition with it. Puccio et al. (2006) mention two important grazers in this area, the sea urchins Paracentrotus lividus (de Lamarck, 1816) and the black urchin, Arbacia lixula (Linnaeus, 1758).

It should be noted however that Deudero et al. (2005) observed that food selection appeared opportunistic with algae as well as pagurids and polychaetes taken. Although Puccio et al. (2006) argued that given the scarce occurrence of such items in the stomach they were not being specifically chosen. He backed up this analysis showing the chelae to be shaped like those of vascular plant eaters. In addition the gastric mill (part of the digestive tract of crustaceans) contained structures which corresponded to those found in grazers not predators.

The consensus of opinion on how Percnon gibbesi entered and spread in the Mediterranean seems to be that it was introduced through surface currents and then had its dispersal accelerated by ship borne transport (Yokes and Galil 2006, Pipitone et al. 2001, Galil et al. 2002). It’s likely that Percnon gibbesi came through the Strait of Gibraltar as the population in the Mediterranean shares similar morphological characteristics with those found in the Atlantic (Pipitone et al. 2001).

Conversely Abello et al. (2003) suggested its larvae entered with Atlantic currents and then dispersed naturally, However although the crab has a long larval lifespan of up to 6 weeks, data in support of a coastal transport mechanism able to explain its rapid spread is limited (Yokes and Galil 2006). However, no studies have been done to investigate its ability to export larvae over open water (Yokes and Galil 2006).

But Zaouali et al. (2007) argue the spread has, at the very least, been aided by ship transportation stating quite strongly that, “this vessel-transported plagusiid is the single most invasive decapod species in the sea, spreading within a few years from the Balearic Islands to Turkey, possibly via recreational and fishing vessels”.

Because the crab colonises breakwaters and the like with such zeal this propensity may enhance its chance of spread by ship. Its choice of creviculous habitats (Cannicci et al. 2006) and, that just a few ovigerous females might be enough to establish a viable population, may also enable the success of this form of dispersal (Yokes and Galil 2006). Puccio et al. (2006) indicate Percnon gibbesi to be a highly fecund species.

While ship borne dispersal of Percnon gibbesi may well be significant in the story of its spread through the Mediterranean it should be remember that natural dispersal will also account for some of its distribution. Thessalou-Legaki et al. (2006) in a study of the Sally Lightfoot in Greek waters notes that while shipping is a possible vector the larvae may also have rode currents across the Ionian Sea. The locations inhabited by Percnon gibbesi on the Hellenic Arch indicate this is a reasonable assumption. They go onto to suggest that it’s presence and algivorous feeding habit in the oligotrophic environment here may prove advantageous.

The larvae of Percnon gibbesi play another role in its phenomenal success in the Mediterranean (Puccio et al. 2006). It produces a very large megalopa and consequently a robust first crab (Paula and Hartnoll, 1989).

Needless to say, Percnon gibbesi is now considered “established” by CIESM (the Mediterranean Science Commission). This means that there are published records of them from at least two different localities (or in different periods), evidence which indicates the population is self-maintaining.

The impact of this new and significant presence in the infralittoral of the Mediterranean on either higher or lower trophic levels has yet to be investigated.

References:

Abelló, P., Visauta, E., Bucci, A. & Demestre, M., 2003. Noves dades sobre l’expansió del cranc Percnon gibbesi (Brachyura: Grapsidae: Plagusiinae) a la Mediterrània occidental. Bolleti de la Societat d’Historia Natural de les Balears, 46, 73–77.

Cannicci, S., Garcia, L. and Galil, B. S., 2006. Racing across the Mediterranean – first record of Percnon gibbesi (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) in Greece. JMBA2 - Biodiversity Records. Published on-line at: www.mba.ac.uk/jmba/pdf/5300.pdf

Cambell, A. C., 1982. The Hamlyn Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the Mediterranean Sea. Hamlyn 320p.

CIESM (the Mediterranean Science Commission)

The CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species is the first attempt to provide a comprehensive, group by group, survey of recent marine "immigrants" in the Mediterranean, which is undergoing drastic and rapid changes to its biota. Go online to:

http://www.ciesm.org/online/atlas/index.htm

Deudero S., Frau A., Cerda M., Hampel H., 2005. Distribution and densities of the decapod crab Percnon gibbesi, and invasive Grapsidae, in western Mediterranean waters. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 285: 151-156

Galil, B. S., Froglia, C. and Noël, P., 2006. CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean. Vol. 2. Crustaceans: decapods and stomatopods, Check-list of exotic species. http://www.ciesm.org/atlas/appendix2.html.

Galil B, Froglia C and Noel P., 2002. Vol. 2. Crustaceans: decapods and stomatopods. In: Briand F (ed) CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean. CIESM Publishers, Monaco, 192 p

Paula J and Hartnoll R. G., 1989. The larval and post-larval development of Percnon gibbesi (Crustacea, Brachyura, Grapsidae) and the identity of the larval genus Pluteocaris. Journal of Zoology London 218: 17-37

Pipitone, C., Badalamenti, F. and Sparrow, A., 2001. Contribution to the knowledge of Percnon gibbesi (Decapoda, Grapsidae), an exotic species spreading rapidly in Sicilian waters. Crustaceana 74(10): 1009-1017

Puccio V., Relini M., Azzurro E., Orsi Relini L., 2006. Feeding habits of Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) in the Sicily Strait. Hydrobiologia, 557: 79-84.

Thessalou-Legaki, M., Zenetos, A., Kambouroglou, V., Corsini-Foka, M., Kouraklis, P., Dounas, C. and Nicolaidou, A., 2006. The establishment of the invasive crab Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) in Greek waters. Aquatic Invasions, Volume 1, Issue 3: 133-136

Yokes, B. and Galil, B. S., 2006. Touchdown - first record of Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) from the Levantine coast. Aquatic Invasions, Volume 1, Issue 3: 130-132

Zaouali, J., Souissi, J ben, Galil, B. S., d’Udekem d’Acoz, C., and Abdallah, A ben, 2007. Grapsoid crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) new to the Sirte Basin, southern Mediterranean Sea—the roles of vessel traffic and climate change. JMBA2 - Biodiversity Records. Published on-line at: www.mba.ac.uk/jmba/pdf/5770.pdf

Peter Barfield (November 2007)

Citation: This article was originally published in the Winter 2007 edition of the Porcupine Marine Natural History Society Newsletter and can be cited as follows:

Barfield, P. D. (2007). Notes on the immigrant, Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne-Edwards, 1853), in the Mediterranean. Porcupine Marine Natural History Society Newsletter, No. 23, 16-17. ISSN 1466-0369.

Note: All images presented here were taken in subsequent years.

© Sea-nature Studies, 2007. All rights reserved in all media.

| pn23winter2007_tipgm.pdf |